San Juan Island Where to Take Yard Waste

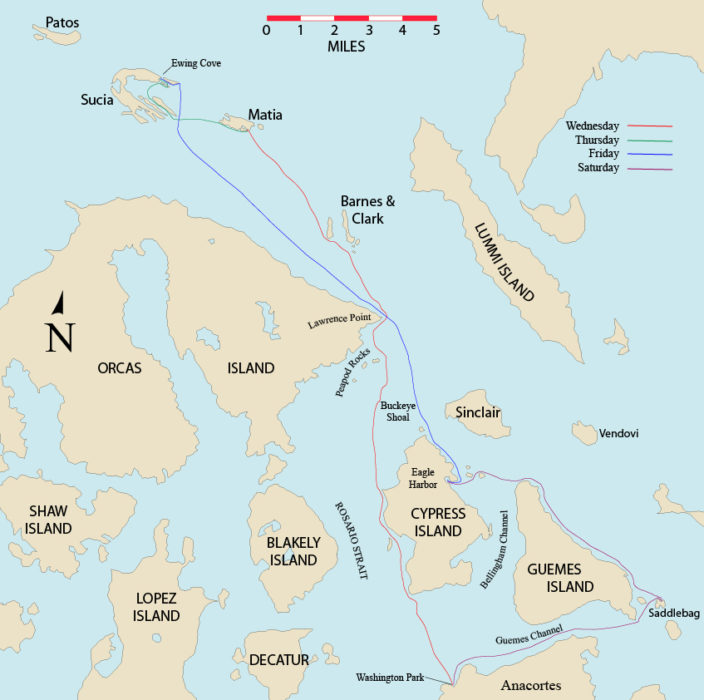

I had timed my launch for the afternoon slack tide; it was a late start, but at midday the ebb pouring through Rosario Strait would have been running against me at close to 3 knots. There were 18 miles to go to reach Matia, Sucia, and Patos, three small islands that crown Washington state's San Juan archipelago, but I'd make good speed with the flood in my favor and my 2.5-hp, four-stroke outboard pushing HESPERIA, a 17′ camp cruiser I'd designed and built. My course paralleled the undulations of Cypress Island's west shore up to the cusp at Tide Point and there I began a diagonal crossing of the strait to Orcas Island. In the open water the tide was with me but the wind was not and as light as it was, it still made a mess of the water. All around the buoy at Buckeye Shoal the waves were as ragged as rasp teeth. It wasn't the kind of water that agrees with HESPERIA's pram bow and shallow-V forward sections. At first I took just a bit of spray over the bow so I just partially unfolded FAERIE—my 4′8″ collapsible, coracle-like tender—like a dodger to keep myself dry. I soon retreated through the cabin to get my weight out of the bow and steered standing in the open hatch. It was still an uncomfortable ride so I veered west toward a bit of flat water on the downstream side of North Peapod, the largest of a cluster of rocks a half mile out from Orcas. I considered abandoning my plan and seeking the more sheltered waters between Orcas, Blakely, Lopez and Shaw Islands but just north of Lawrence Point there was an end to the chop.

Passing within 75 yards of Little Sister, a ragged islet bare but for a few patches of wind-shorn scrub, I steered between mushrooming boils and dimpled eddies toward Barnes Island. Beyond Barnes, the four-mile crossing to Matia offered smoother waters that slipped docilely under the bow. I didn't turn on my GPS to check my speed; the overlapping hills of Orcas Island showed HESPERIA was making progress and that was enough: There was plenty of daylight left, I was where I wanted to be, and it didn't matter how fast I was going. Matia and Sucia were drawing near while behind me the Cascade mountain range, a dusty blue deckle edge spanning the eastern horizon, was flattened and faded by distance.

I had been to Matia a few times before and had hiked by a small pocket cove on the south side of the island. A few dozen yards from the mouth of that cove I cut the motor and cocked it up, crouched through the cabin, and rowed to a band of gravel nestled in a 30′ gap between rock outcroppings. With HESPERIA pulled up just high enough to keep her from floating away, I picked my way across a tangle of sun-bleached driftwood. Among the long bark-bare poles and fluted trunks, two baguette-sized sticks caught my eye. I pried off long slivers to get beneath the silver-gray punk on the outside. The sticks were, as I'd suspected, both cedar, one western red and the other Alaska yellow. I took them back to HESPERIA as much for their fragrance as their usefulness as kindling.

The little cove, I'd decided, was too close to open water to afford much protection for anchoring overnight so I rowed around the southeast corner of the island and into Hermit Harbor.

All photographs and videos by the author

All photographs and videos by the author Once the cabin top is raised, the saloon has 17 windows though which to take in the view. The lower pair here open onto the aft cockpit.

There was plenty to do before I turned in for the night. To raise the cabin roof, the spars came off and were set across the cockpit. I lay down in the cabin, put my feet against the ceiling and pushed the cabin top up until the hinged struts in the corners swung down and supported it. With the stovepipe in place I could start a fire in the wood stove. The cedar kindling lit quickly and orange flames were soon glowing through the stove's mica window. With the middle sections of the cabin doors in place, the cabin warmed up. Not wanting to take time to make a proper dinner, I set a pot on the stove to boil water for a camping meal that cooks in its zip-lock bag. I set the floorboards on the ledges that hold them flush with the benches, rearranged the cushions and made the bed: clean sheets, a down comforter, and the pillow I use at home.

Inside each bench cushion there is 3" of camper-pad foam on top of ¼" of closed-cell foam—good enough for sitting—but for sleeping, 1½" Therma-rest pads slipped underneath the cushions add a welcome measure of comfort.

By the time I was ready to push off the beach and anchor, it had grown dark and the woods that wrapped around the cove were a sooty fringe for a starlit sky. The first dip of the oars in the water set the blades aglow with pale blue light. About 50 yards out, I slipped the anchor over the bow and watched the bioluminescence wrap around it like an alcohol flame.

In the morning I unfolded FAERIE, put her over the side, and paddled ashore. The half-mile trail across Matia meanders around tall cedars and pines that knit a lofty canopy so tight that only speckles of sunlight reach the forest floor. Olive-drab and licorice-black slugs traced cellophane-clear tracks across the trail and moss flocked the tree trunks and boulders. The dock at Rolfe Cove at the west end of the island was empty; I had Matia all to myself.

With HESPERIA at anchor, I paddled my folding tender FAERIE ashore on Matia Island.

Back aboard HESPERIA, I spent a leisurely morning getting ready to row to Sucia Island. After breakfast I stowed the bedding, did the dishes, polished some of the silver, and shook the rugs out. The water in the cove and as far as I could see beyond it was slick and bright; without any wind in the offing I could leave the cabin up, snap the canopy in place over the cockpit and row to Sucia in the shade.

The south side of Matia is a band of ragged cliffs about 20′ high, not quite as tall as the trees perched on top of them. Eroded sandstone walls are pocked with irregular cavities arrayed like hollows in airy leavened bread. In the currents swirling off Eagle Point, the western extremity of the island, an outboard skiff drifted slowly with four fishermen aboard, each occupying a corner of the cockpit with his back to the others, a rod in hand, and head bowed as if in prayer.

Decked out for a day in the sun, HESPERIA has her canopy in place over the cockpit, a shower bag hanging from the gallows, and two solar panels charging overhead.

There was a slight current setting me to the south as the ebb sifted itself through the islands so I angled the bow northward to keep on course. Harbor porpoises worked the tide rips, showing only their backs, curved like ulu blades cutting upward through the water. I reached Sucia at its southeast corner where its slender peninsulas and islets are arrayed like the tines of a fork. As I entered Echo Bay the current grew stronger so I hugged the shore, keeping my starboard oar just a few feet from the rocks. I crossed to the Cluster Islands that separated the bay from Ewing Cove; the low water had joined several of the islets into a peninsula but there was a gap just wide to get through, though I'd have to hop my port oar blade over an ottoman-sized rock that sat in the narrowest part of the passage. The current was strong but I'd built up enough momentum to carry past the rock, get the port oar back in the water and keep working my way upstream.

Ewing Cove is well separated from Sucia's more heavily used anchorages and campgrounds. It gets lots of visitors during the day but few, if any, stay the night.

Ewing Cove's shallows were covered with chocolate-brown fronds of seaweed that reflected the sunlight in glimmers of iridescent blue. I found a patch of sand for the anchor and back-paddled at the end of a short rode until the flukes had buried themselves. After paddling FAERIE ashore I walked 1½ miles along the dirt path that weaves in and out of the woods along the margin of Echo Bay.

Back aboard HESPERIA I set to work making dinner. It would be a bit more elegant than the last night's meal out of a bag and I eventually sat down to a tuna steak, pan-seared with sun-dried tomatoes; steamed asparagus spears under a thick pat of butter; a green salad with kale, dried cranberries, toasted pumpkin seeds, and poppyseed dressing; coconut water with bits of coconut meat; and a small chocolate truffle cheesecake.

It's well known that even the plainest meals taste better in the wilderness and it should, of course, go without saying that sterling silver is an unnecessary extravagance aboard a small boat. Silver plate is more than adequate.

The solar heated shower bag that had been out all day had warmed up a couple of gallons of fresh water, and now that all of the kayakers and walkers who'd visited the cove during the afternoon were gone, I could shower in the cockpit and then retreat to the cabin to dry off in the heat of the stove.

On the north side of Ewing Cove there's a 75-yard wide gap between Sucia and tiny Ewing Island and the tide flushing through creates an eddy running parallel to the beach that would set HESPERIA beam-to waves entering the cove from the east. To keep her from rocking all night as she would surely do even with sets of small waves, I tied the main sheet, the mizzen sheet and a few other lengths of line together as a stern line and paddled FAERIE ashore with it. Pulled tight and tied to driftwood, the line set HESPERIA across the current with her bow facing the entrance to the cove. The difference was quite noticeable—HESPERIA was serenely steady—and I would have slept soundly the whole night through if not for the midnight squabbles of Canada geese.

A mahogany cover converts the sink into a breakfast nook. The gypsy flowers, hastily carved of red cedar and yellow cedar driftwood, were as fragrant as any blossoms. The spork is, I confess, a silly affectation. I have plenty of room aboard HESPERIA to carry a separate spoon and fork and needn't put on airs as if I were through-hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. The spork was, I should add, utterly useless for eating a fried egg, over easy, on a toasted bagel half.

In the morning, after breakfast, I got a fire going, set a collapsible water jug on the cabin roof to supply HESPERIA's plumbing, and filled the sink with hot water for a shave. I've tried going without shaving on previous cruises but my encounters with strangers led me to understand that a few day's growth make me look more feral than outdoorsy and clean-shaven I elicit kindness more than fear.

Only the sink is plumbed for hot (via a heat exchanger on the wood stove) and cold running water. The head, stowed out of sight in a compartment in the cockpit, is a portable rig with its own water supply and the bathtub, a soft-sided PVC liner for the cabin footwell, is used in conjunction with pots of stove-warmed water.

My plan was to continue west to Patos Island and spend my last night there. The crossing from Sucia is a short one, only 1 ½ miles, but when I motored along Ewing Island on my way out of the cove I saw a small outboard cruiser right where I was going to make the turn to head east to Patos. It was pushing a foaming white bow wave but making barely 2 knots over the bottom. My little 2.5-hp outboard would be no match for the current so I turned south across Echo Bay to consider my options. The wind coming across the bay was from the northwest and perfect for beginning my homeward leg. I killed the motor and went forward to raise the main mast; for the downwind run I'd leave the sprit main wrapped around it and use the jib halyard to raise the square sail. It billowed forward and HESPERIA steered herself, setting a course for the far corner of Orcas Island, exactly where I wanted to go. I stretched my legs out on the starboard bench and leaned up against the cabin, keeping only a light touch on the tiller line. Matia slipped by to port and Mount Baker's sugar-white flanks gleamed under the lower yard.

The wind was light at first but halfway through the nearly 9-mile run to Lawrence Point, it strengthened, and HESPERIA was making 5 1/3 knots. After picking up a bit of ebb beyond the point we passed Buckeye Shoal making 7 knots over the bottom. The wind carried HESPERIA as far as the north end of Cypress. The square sail had made quick work of the 13-mile run and left me with only 2 miles of motoring to reach Eagle Harbor.

Cypress Island's Eagle Harbor has broad mud flats at the head of the cove. While there were a dozen or more boats anchored nearby, no one else, oddly enough, had come ashore.

There were several boats anchored at the mouth of the bay but no one had ventured into the shallows. Perched on the foredeck I paddled ashore, stepped off, and post-holed across the mud flats with a long painter and a stake in hand. With HESPERIA tethered, I crossed the beach and walked a path so hemmed in by trees and brush that there wasn't much to see; after just a few hundred yards I turned around. I gathered some nettles on my way back to the boat. They're the limit of my foraging skills: I'm never sure about plants I think I know on sight, but nettles picked with bare hands provide an unmistakable sting.

I thought I could do better than labor through the mud back to HESPERIA and did a little beach combing for materials to cobble together some snowshoe-like footwear to keep me from sinking. I found a short length of line and two slats of driftwood. I unlaid the line and used two of the strands to tie the slats to my feet. They worked like a charm and kept me right up on the surface for most of the length of the mud flats but then got progressively stickier. With each step the trailing foot was harder to pry free, and the more I pulled, the more deeply I mired my lead foot. Soon I had both feet firmly glued in place, just two yards from the edge of the rapidly advancing tide. I had tied the line as tight as I could to keep the slats from falling off and didn't have enough length to slip any of the knots. The knots were over my heels so I couldn't see what I was doing and my fingertips, still stinging from my nettle harvest, were, in essence, quite numb. I stood up, a bit perplexed, thinking about a pen-and-ink illustration I'd seen in a WoodenBoat magazine article on shoal-draft cruising. It showed a boy running across the mud wearing splatchers, a fancier shop-made version of what was, at the moment, using me as bait for the incoming tide. All too often I've gone ashore without a knife, an oversight that I'd often regretted, but never more than now. I patted myself down and discovered a small folding knife in my pants pocket; I cut myself out of the bindings, stepped off the slats into shin-deep mud and slogged back to the boat.

After paddling out to anchor, I picked a spot in the shallows, well away from the other boats. The sun had not yet pushed the shadow of Cypress's ridge across the cove so I set up the kitchen in the cockpit, steamed the nettles, cooked up a stir fry, and took my dinner al fresco. The nettles were a disappointment; they had neither the peppery attack nor the buttery artichoke finish they would have had a month earlier.

Setling in for the night, I fired the stove with the yellow cedar gathered on Matia; it put out so much heat I had to open the cabin doors and the hatch and step outside to cool off. Eagle Harbor was so still that I could get a good look at Jupiter through my binoculars and make out two of its moons. When the cabin was comfortably warm I was in no rush to crawl into bed and sat on the comforter with my pillow at my back, stared at the orange glow of embers behind the stove's widow, and idly worked my way through a bag of pistachios. When I began to feel drowsy I tossed the mound of shells into the stove, turned out the lights and slipped under the covers.

There wasn't a breath of wind when I left Eagle Harbor, but I set sail and motored out to find a breeze.

I was up early. The rapid knocking of a woodpecker somewhere in the woods was the only sound and it filled the cove. After a long silence an owl hooted its two-note ooo-hoo, clear and loud although more than 100 yards of water separated me from the woods. There was not a breath of wind but I rigged for sailing in the hopes of finding a breeze somewhere around Guemes Island. With main, jib, and mizzen up, I motored out into Bellingham Channel. Halfway across there was a patch of water scuffed by a breeze; I motored into it and sailed on a reach the remaining distance to Guemes. After rounding the north end of the island I had the wind behind me; it was light, and HESPERIA ghosted along under a high haze that put a faint rainbow ring around the sun. The jib didn't have enough wind to draw its sheet tight so I dropped it and used the halyard to raise the square sail. It filled and drew nicely even though half of it was blanketed by the main. I thought I could get more of the sail out where it could do some good by slipping the lower yard to port through the loosely tied truss holding it against the mast. It worked and when the wind freshened I was making 4 ½ knots.

Saddlebag Island lay a mile to the east of Guemes, and although the wind had dropped enough to leave the water glassy, I made good headway on a reach under main and mizzen. When I arrived at the cove notched in the island's north side I let the sheets loose and aimed for the beach. It appeared to be sandy, but I sat on the foredeck as I came in to keep an eye out for rocks. There were many and I slipped off the bow before running aground and held HESPERIA off. Behind me someone spoke my name. It was my friend Ted, an experienced paddler and a fixture in the local outdoor recreation industry. He and a friend waded in and held on to HESPERIA. I was going to have to anchor to visit the island and invited them both to climb aboard. We paddled out about 20 yards and dropped the hook. To get us all back to shore I unfolded FAERIE and had them paddle in one at a time, trailing a long tether so I could pull FAERIE back. I came ashore last, visited a while, and took a brief walk across the island's wasp waist to the cove on the south side.

When I left Saddlebag there wasn't any wind; as I motored west I dropped the rig and stowed it on the cabin roof. With the current in my favor I made 6 knots over the 7 miles back to the launch ramp Washington Park and when I arrived there, HESPERIA had carried me in comfort for 55 miles. By dusk, I'd be back home, in a house that hasn't moved an inch in 88 years, and HESPERIA would be in the driveway, covered by a tarp.

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Monthly. He built a Chamberlain dory skiff in 1979 and rowed and sailed it 700 miles up British Columbia's Inside Passage. In the fall and winter of 1983 he paddled 2,500 miles from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico in a canoe he'd made of laminated paper. Two winters later he rowed a sneakbox 2,000 miles from Pittsburgh to New Orleans and continued another 400 miles under oars and sail to Florida. For a 1,000-mile rowing/sailing trip up the Inside Passage in 1987, he built a replica of the ninth-century Gokstad Faering.

HESPERIA

I've cruised thousands of miles in small boats and endured some miserable conditions, but I never had a Scarlett O'Hara moment: "As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again." I was slow to catch on; the adventures that made me hungry, cold, wet, and tired only gradually lost their appeal and with each new boat I built for cruising I incrementally eliminated sources of discomfort and displeasure. I was quite happy with my Caledonia yawl ALISON as a camp-cruising boat until my son built BONZO, an Escargot canal cruiser. I decided I needed a cruiser like BONZO with a cabin, windows, and woodstove, but one that I could sail, motor and row like ALISON. I gave up the Caledonia's rough-water ability for a boxier hull that could stay on a nearly even keel no matter where weight was placed, especially for dining and sleeping. I was drawn to Phil Thiel's APHASIA, which he describes as a sampan-type hull. I enlarged the hull by 8 percent and modified the bottom to put some vee in the forward sections. It was a roundabout way of arriving at a garvey hull.

The hull went together quickly and I designed the interior as I went along, occasionally making sketches but more often using sticks and cardboard to mock up the accommodations. I had to get the hull out through a door, so the cabin was made to be removable. The centerboard trunk is placed off-center to keep it out of the way; it's incorporated into the benches in the cockpit and cabin.

The cabin is built like a pop-top camper shell for a pick-up truck. Lowered, it provides a clear line of sight aft while I'm rowing; raised, it has good clearance for sitting in the cabin. I raise and lower the top by lying on my back and pushing the ceiling with my feet. Hinged support struts in the corners fall into place when the cabintop is raised. The doors have a removable center section to accommodate the 11″ of the cabintop's travel.

In one corner of the cabin, a shelf supports a wood-burning stove I welded together from sheet steel; in the other corner there's a small sink. A collapsible water jug set on the roof connects to the cabin's plumbing and a heat exchanger made of copper pipe butts against the stove to provide hot water for the sink.

The passageway down the center of the cabin and cockpit has parallel sides and ledges to hold floorboards flush with the benches to create sleeping platforms in both the cabin and cockpit. Grabrails on the cabin roof are spaced to fit the cleats under the floorboards so they can be used as a catwalk or a sun deck.

A tiller line runs through the cabin and around the cockpit and another line connects to the outboard's kill switch. Having the motor and cockpit separated by the cabin cuts down on the noise. The cabin sides have ports that open to thole-pin pads for rowing indoors in cold, wet weather.

The masts and the main's sprit and boom are all about 12′ long and can be stowed in the boat. The cabin's windage gave the sail plan I'd drawn more of a weather helm than I like so I added a self-tending jib on a club for better balance. The jib, main and mizzen were all cut from the protected Dacron in the middle of a weathered roller-furling jib discarded by a larger sailboat.

The square sail was inspired after taking this same San Juan Island trip with my ladyfriend Rachel. I had, as is my habit, loaded the boat and set out without stowing things properly. We were motoring along Rosario Strait when a strong following wind developed. Rachel was napping in the cabin and I tried to set the sprit main by myself without first setting the mizzen and luffing. Every time I tried to clip the main sheet into the boom, the boat would veer off course. In my struggle I didn't realize that I'd stepped on our dinner—a deli box of hot polenta—until I felt the corn mush squeezing between my toes. Tangled up in the main sheet, I decided to sit down and give up before I got pitched overboard. Rachel appeared in the cockpit with a spoon, reshaped the box, carefully scraped the polenta from my foot and the floorboards and put it back in the box, assuring that we wouldn't go hungry that evening. After that trip I made the square sail specifically for taking advantage of an unexpected following wind: It goes up in an instant and the boat practically steers itself.

| LOA | 17′ |

| Beam | 6′ |

| Depth | 25 ¾″ |

FAERIE

HESPERIA, laden with cruising gear, is too heavy to move if the tide goes out from under her, and with tides in my area ranging up to 14′, constant tending is required when she's nosed up to a beach. I've used a few systems to put the boat at anchor from shore, but they are all time-consuming and require very long lines. I wanted a folding dinghy that I could stow out of the way in the cockpit, so the fit there determined its dimensions. The only boat I knew of that small was a coracle but while studying the type I came across the Fliptail, a dinghy that was very close to what I had in mind: a skin boat with a folding frame. I laminated bows that would fit the forward end of HESPERIA's cockpit.

Folded, FAERIE tucks into the forward end of the cockpit, taking up a minimal amount of space. Grab rails on the roof hold cabin floorboards in place.

The Fliptail uses hinges, but I couldn't find any that were the right size, shape, material, and price. I sketched many schemes for using bolts as pivots before figuring out the geometry that would do the job. The skin is Hypalon I had from an old pool liner. A plank set across the gunwales serves as a seat and if I need floorboards for a passenger or cargo, HESPERIA's dining table is a perfect fit. The high freeboard gives FAERIE surprising carrying capacity. I've paddled with my son sitting in the stern, and our combined weight is about 415 lbs.

FAERIE feels a bit tippy with the paddler's weight carried so high, but I haven't yet capsized her. On beaches with a moderate slope I can paddle up to the water's edge, lean back quite confidently and set the bow just barely up on the land and step out with dry feet. I used a zig-zag sculling stroke at first but later discovered old film footage of coracles ( Boyne Coracle, A Bygone Craft, and Peeps though a Window of the World) being paddled with a draw stroke and the blade slashing in an out of the water from one side. It provides much more power and drives the little hull as fast as it'll go, which is about 2 knots.—CC

| LOA | 56″ |

| Beam | 40½″ |

| Depth | 14½″ |

If you have an interesting story to tell about your travels in a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

San Juan Island Where to Take Yard Waste

Source: https://smallboatsmonthly.com/article/san-juan-island-solo/

0 Response to "San Juan Island Where to Take Yard Waste"

Post a Comment